Thailand in a Changing World Order: How Will Thailand’s Engagement with ‘Minilateralism’ Shape Its Relations with the Mekong Subregion? | Narut Charoensri

Thailand in a Changing World Order: How Will Thailand’s Engagement with ‘Minilateralism’ Shape Its Relations with the Mekong Subregion? | Narut Charoensri

วันที่นำเข้าข้อมูล 18 Nov 2024

วันที่ปรับปรุงข้อมูล 18 Nov 2024

.jpg)

No. 3/2024 | November 2024

Thailand in a Changing World Order: How Will Thailand’s Engagement with ‘Minilateralism’ Shape Its Relations with the Mekong Subregion?

Narut Charoensri*

(Download .pdf below)

The international order is currently being significantly challenged, and this has become a critical issue that scholars of international relations are striving to examine. They are analysing the patterns of the prevailing international order, its inherent problems, and the emerging orders being proposed by other countries, such as Russia, China, and India. The challenges to the existing international order are impacting the foreign policy strategies of non-major powers, particularly middle and smaller states, as they are increasingly confronted with the dilemma of choosing sides or signalling closer alignment with one bloc over another. This has complicated the efforts of these states to formulate their own strategic policies, as the international order imposes conditions and a contextual environment that substantially shape the development of foreign policy for middle and smaller states.

In the case of Thailand, it is a middle power that plays a pivotal role in the Mekong subregion. Thailand’s central location in continental Southeast Asia enables it to connect supply chains with various countries easily. Thailand’s economic growth rate, natural resources, people, and culture, along with other attractive factors such as the educational level of its population and the development of its infrastructure, are all conditions that create significant opportunities for Thailand to assume a leadership role in the Mekong subregion. However, certain factors may limit Thailand’s capacity to adopt such a leadership role. These include domestic challenges, such as political instability, economic problems, and an ageing society that affects productivity, as well as the middle-income trap. Furthermore, external factors at both the subregional and regional levels, particularly the shifting international order, play a significant role in determining the conditions under which Thailand can assert its leadership in the region.

The prevailing international order is a liberal democratic one, primarily established by the United States. The development and consolidation of this order have been shaped by the continuous creation of international institutional mechanisms since 1945, along with the deep entrenchment of liberal political ideologies. These ideologies include liberal democracy, respect for human rights, and openness in both economic and political spheres. The political and economic regimes that have emerged from this framework have significantly influenced the conduct of international relations, as they have established international norms that define the values, principles, and ideas considered to be the fundamental ideologies of the international political system. These international norms have shaped the mechanisms, institutions, behaviour, and foreign policies of states and international organisations, acting as frameworks that compel countries operating within these regimes to comply with their standards.

However, the issue in international politics today is that the liberal democratic order is being challenged by a variety of factors, including:

1.1 The world has increasingly become a multipolar one. This is due to the rise of countries with growing economic, political, or security power in global politics, meaning that the United States is no longer the sole superpower in the international political system. The emergence of new actors is not limited to states from the First World or developed countries, but also includes states from the Global South, often referred to as developing countries. These states possess distinct political and economic characteristics and experiences, leading to differing perspectives on global development, strategies for national growth, and questions about how they might fit into the liberal democratic international order. The suitability of this order is being questioned, as it may not align with the unique contexts of these states or regions, which could be considered sui generis.

1.2. The way in which global dynamics are perceived has become a crucial factor. With more actors on the world stage, how one interprets these developments is key. Some may view this shift as an opportunity for increased cooperation, whilst others may see it as a potential driver of greater conflict. We have already observed that many global policymakers perceive the rise of new actors as a source of competition, seeing this as a challenge to the power of the United States, which has long held a hegemonic role within the liberal democratic international order.

1.3. With these changes and the rise of new actors, there arises the question of whether the existing political and economic values still serve the interests of the states and regions in question. If they do not, the next challenge is to explore whether there are viable “alternative options” that can better meet their needs.

Scholars such as Schirm (2023) have proposed that the emerging global order could be termed the “Southern World Order”, whilst Flockhart and Korosteleva (2022) refer to it as a “Multi-Order”. These perspectives exemplify the viewpoints of scholars who are attempting to analyse the origins of this new global order and its implications for the resistance, opposition, acceptance, or adaptation of states to the evolving order. It is not only the foreign policies of middle and smaller states that must adapt, but these emerging dynamics also influence the web of regional and subregional relations in which such states are embedded. In other words, when the global order shifts, middle and smaller states are affected in two key areas:

- Their foreign policies towards other states and issues.

- Their policies and relationships within existing frameworks of multilateralism, minilateralism, or regionalism.

This piece focuses on analysing the changes in the second set of relationships. The primary question guiding this work is: as the international order undergoes a period of contestation, what issues should Thailand prioritise, and how should Thailand navigate the evolving international order? The arguments are twofold: (1) Thailand’s engagement in ‘economic minilateralism’ (e.g., RCEP, OECD, IPEF), ‘political and security minilateralism’ (e.g., AUKUS, QUAD, BRICS), and ‘hybrid frameworks’ (e.g., MLC, MUSP) is not merely about ‘side-taking’ with a focus on ‘national interests.’ Rather, it represents the articulation of its strategic positioning—encompassing both interests and values—within the international system; and (2) therefore, the relevant questions should examine the significance of the current international order, particularly its characteristics and limitations, and how these shape Thailand’s vision and national interests.

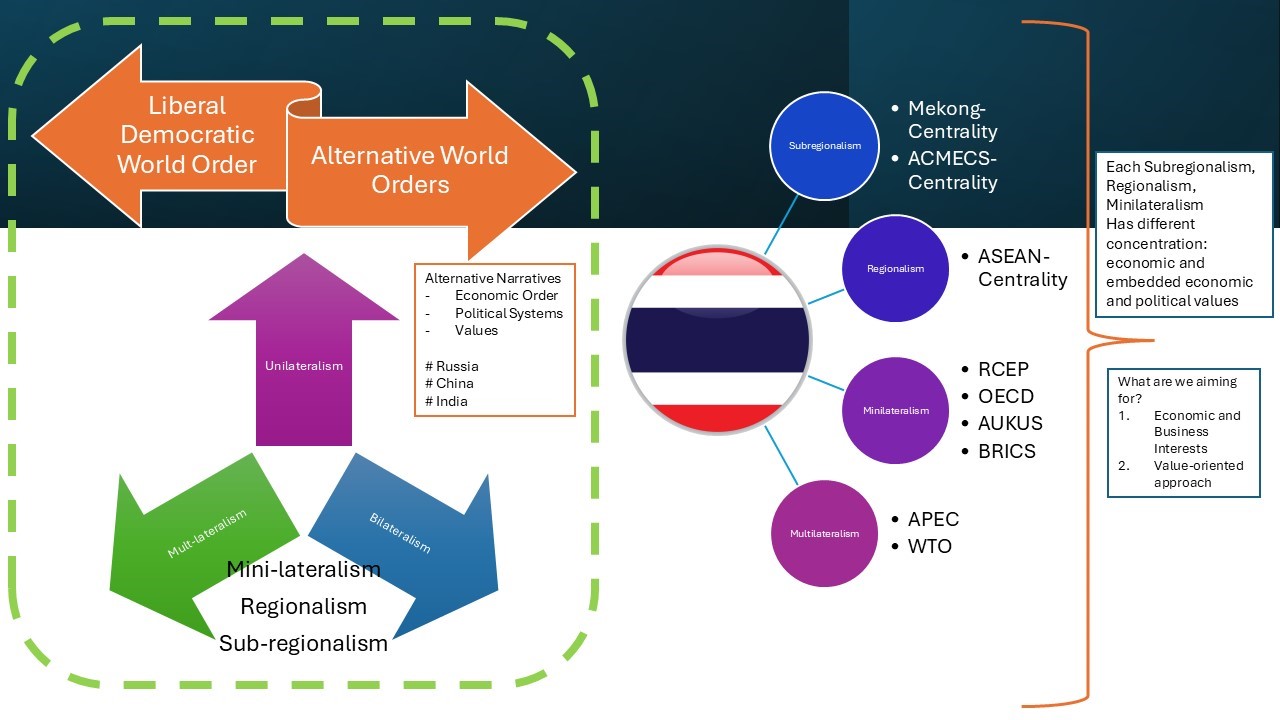

Source: Author

I would like to begin by analysing the diagram I have developed, in order to illustrate the situation in which the world is facing a transformation in the international order. I will explain it progressively, from the left to the right side of the diagram.

To start, I would like to highlight, as mentioned earlier, that the liberal democratic international order is being challenged by alternative international orders proposed by China, Russia, and India. These countries have offered explanations regarding the problems inherent in the liberal democratic order established by the United States. The proposals put forward by China, Russia, and India each attempt to construct a narrative about the flaws in the existing order and the possible alternatives for conducting international relations. This perspective allows middle and smaller states to recognise the challenges they face, whether in terms of international security, economic issues, or alternative approaches to international relations.

For example, the capitalist system’s impact on modes of production, livelihoods, and the development of economies and people’s lives has raised concerns. Issues such as human rights, the role of the United States as the world’s police force, and the various frameworks of cooperation at the international, regional, and subregional levels each have their own distinct problems. One of the key issues is the influence of capitalist thinking, which has resulted in overproduction, environmental degradation, a focus on market-driven approaches, and the neglect of issues related to justice and equality. Furthermore, there is criticism of how some states perceive the violation of internal values and principles, which they regard as unique to their specific context. Similarly, the United States' encroachment on the sovereignty of other states in the name of democracy and human rights has also been questioned.

These challenges have led to the emergence of new approaches to international relations, particularly amongst major powers like China, Russia, and India. At the same time, middle and smaller states are compelled to consider their roles amidst the competition between the old and new global orders. These states must find ways to establish their stance, protect their interests, and maintain their strategic sovereignty.

As the context of international relations undergoes change, we are also witnessing parallel shifts in the forms of international cooperation between states. Countries are increasingly seeking cooperation at the global, regional, and subregional levels, based on three broad principles to achieve their goals:

- To establish norms and order: International cooperation aimed at creating norms and practices that contribute to a shared system of rules and order, such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO).

- To create rules and frameworks for specific objectives: Cooperation that is focused on achieving specific goals, where the primary concern is not the location or characteristics of member states, but rather the shared objectives they seek to accomplish, whether they pertain to economic, political, or security-related goals.

- To address specific regional challenges: Cooperation based on geographical proximity, assuming that states in the same region face similar challenges. This form of collaboration seeks to solve specific issues, which may be economic, political, or security-related, based on the shared concerns of neighbouring states.

Once states determine the rationale for cooperation, the “form” of collaboration arises, whether through unilateralism, bilateralism, multilateralism, or the increasingly prominent form known as minilateralism. These forms of cooperation have evolved with different goals, mechanisms, and approaches to achieving objectives. They provide alternatives for existing members, as well as for states considering whether to join. New members are expected to decide based on their national interests, the international benefits they aim to achieve, and their alignment with the principles, norms, ideas, rules, or forms of cooperation.

In other words, these various forms of cooperation, grounded in alternative conceptions of the international order, have become a strategic option for middle and smaller states as they navigate the complexities of global politics.

In the case of Thailand, as it faces the shifting international order and the accompanying challenges that compel it to choose how to navigate its relations with both the old and new international frameworks, I believe Thailand must also confront and reflect on its own internal challenges. I analyse that the key factors shaping Thailand’s decisions regarding its engagement with the international order are centred around five major issues:

- At the subregional and regional levels: Thai government agencies, such as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, have consistently sought to position Thailand as a leader in the Mekong subregion through the promotion of the Ayeyawady-Chao Phraya-Mekong Economic Cooperation Strategy (ACMECS), established in 2003, as the primary framework for coordinating development efforts in the Mekong subregion. Simultaneously, Thailand has pushed for the importance of ASEAN Centrality, especially as ASEAN engages with Dialogue Partners and interacts with various regional cooperation frameworks that involve major powers such as the United States, China, and Japan. In this context, Thailand faces the question of which cooperation framework it should prioritise to maximise its benefits whilst maintaining its leadership role in the region and responding to regional interests.

- At the level of Minilateralism: Thailand’s participation in the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), its application for membership in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), its expressed interest in joining Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS), and its interactions with the Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States (AUKUS) all serve different purposes, as each framework has distinct objectives. Thailand’s ability to benefit from these frameworks varies across areas such as production, exports, and security. Moreover, Thailand’s engagement with these frameworks reflects different political stances, as each involves major powers with divergent views on the international order. Thus, Thailand’s involvement in or interactions with these frameworks signal differing positions and approaches.

- At the level of Multilateralism: The current multilateral international order exerts significant influence, shaping global economic rules and systems. This raises important questions about the search for alternative pathways, as it challenges the existing international order and its flaws. It also prompts reflection on whether the world can establish new methods, rules, or norms that foster development or economic growth in a more equitable, just, and inclusive manner, taking into account the diverse contexts of different states.

Given this international context, the next question Thailand must consider is how to navigate these changes in a way that allows it to become part of the emerging international order whilst ensuring that this new order can coexist with and support the subregional frameworks Thailand promotes, such as those in the Mekong subregion and Southeast Asia. The key questions Thailand must address are:

1. What role and position should Thailand adopt in the context of the competing international orders?

2. How should Thailand compromise or accommodate these competing international orders to ensure they align with the subregional and regional initiatives it promotes or is a member of, whilst simultaneously safeguarding its national interests?

3. And a question that has perhaps been less studied: What values should Thailand emphasise in international politics, given that each international order is founded on distinct principles and values?

I contend that, in order to address the aforementioned questions, there are three key issues that Thailand may consider as guiding principles when developing its foreign policy in response to the evolving international order:

- Order-based Approach: I believe the central issue facing foreign policymakers is the question of alignment. The question of how Thailand should conduct its international relations to express its stance, or which side Thailand should align with in order to safeguard its national interests, is crucial. I believe the Thai government has managed this issue well thus far. Thailand’s approach of not taking sides, often referred to in theory as “Bamboo Diplomacy”, has allowed it, as a middle power, to protect its national interests. This strategy has long been a core part of Thailand’s foreign policy. Therefore, in the context of the shifting international order, Thailand should continue to pursue this balancing strategy, maintaining bilateral relations with major powers in a way that preserves its national interests.

- Sub-/Regional Approach: To maintain its leadership role in the Mekong subregion and ASEAN, Thailand’s participation in various minilateral frameworks should enhance its ability to leverage the different principles and mechanisms offered by these frameworks. This includes areas such as production, exports, and utilising economic opportunities to position itself as an economic leader in the subregion. Thailand should not only promote mechanisms, rules, and institutions that shape the economic order in the subregion but also encourage new actors to enter the region to create additional opportunities. For instance, promoting Mekong-Russia cooperation or positioning Thailand as a “Regional Knowledge and Capacity Training Hub in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS)” could enable Thailand to use its resources as a “source of soft power”. This would allow the government to utilise soft power to strengthen Thailand’s leadership role and neutrality, helping the country navigate the competition between international orders.

- Value-Based Approach: Beyond economic and political interests, I believe Thailand could play a key role in shaping the international order by engaging with various minilateral frameworks through a values-driven approach. Thailand could position itself as a leader in creating an international forum for discussing the order, values, and principles of Southeast Asia in relation to the global order. This could be similar to ASEAN’s development of the ASEAN Outlook on the Indo-Pacific, which outlines ASEAN’s stance on regional matters. In this way, Thailand could take a leading role in facilitating regional dialogue that establishes values, principles, and norms as key elements of its interactions with various minilateral frameworks. This would also support the concept of ASEAN Centrality, helping to ensure that these principles align with ASEAN’s long-term vision.

In conclusion, I believe the competing international orders have significant implications for middle and smaller states, compelling them to develop foreign policies that align with their national interests. The key question for these states is how they will adjust their foreign policies, strategies, and positions to safeguard their national interests, given the shifting nature of the international order. As mechanisms of international cooperation change, so too must the way states engage with these frameworks. Thailand is no exception. With its geopolitical strengths, economic capabilities, and distinct foreign policy approach, Thailand’s ambition to play a leadership role reflects the need to consider how it can adapt to these surrounding dynamics.

I believe Thailand has great opportunities within this evolving international order, as it presents new possibilities for multilateral cooperation and minilateral cooperation. However, the path Thailand chooses to take is crucial. The key question is how Thailand wishes to present its national interests and political and economic ideologies to the region and the world. This is both a theoretical question and one that requires practical strategies moving forward.

References

Flockhart, T., & Korosteleva, E. A. (2022). War in Ukraine: Putin and the multi-order world. Contemporary Security Policy, 43(3), 466–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/13523260.2022.2091591

Schirm, S. A. (2023). Alternative World Orders? Russia’s Ukraine War and the Domestic Politics of the BRICS. The International Spectator, 58(3), 55–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/03932729.2023.2236937

* Presented at a forum entitled “Thailand’s Choice in Plurilateralism/Minilateralism: A Building Block or a Stumbling Bloc to a Balanced Foreign Policy?” organised by the Institute for Security and International Studies at Chulalongkorn University, Thailand, 24 September 2024. The author would like to express his sincere appreciation to the Institute of Security and International Studies at Chulalongkorn University and the Friedrich Naumann Foundation Thailand for their generous financial support.

** Assistant Professor, Faculty of Political Science and Public Administration, Chiang Mai University.